The Ontario transportation sector is shaken by talk of big data. But what questions should we be asking in these times of data-utopia?

Conversations about data abound in the transportation industry today. The promise is that the ability to capture and process data will enable transit agencies to manage traffic and congestion in real-time to increase the efficiency of moving people and goods. For now, however, these possible futures have to be seen against the political, social and economic realities of Ontario cities and algorithmic planning more broadly.

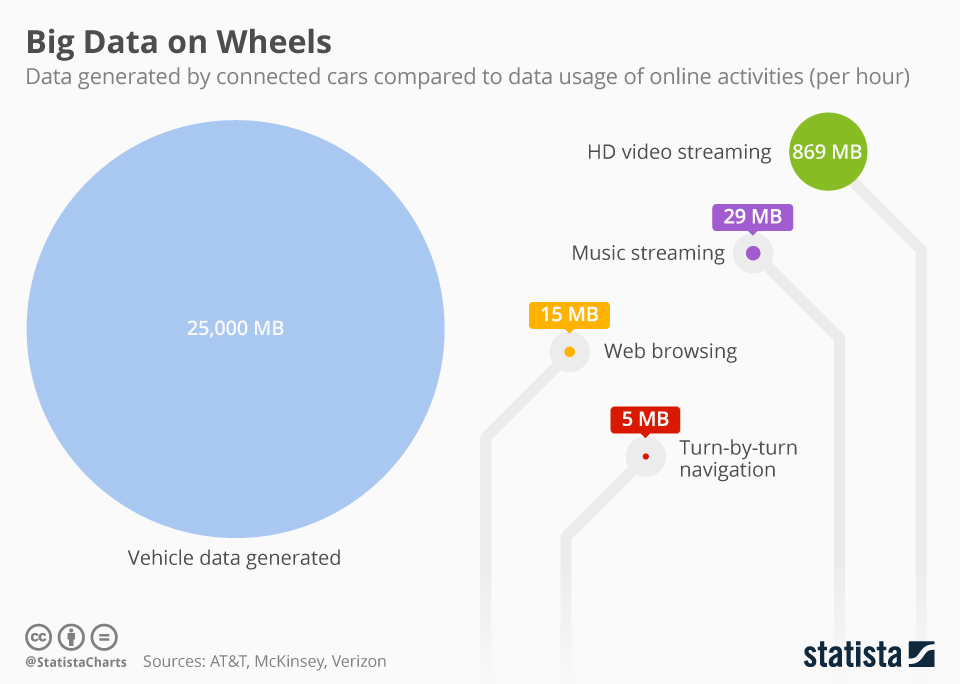

Public transportation agencies generate large amounts of data as part of their daily

operations. Automatic Vehicle Location systems track the positions of buses and trains and collect a constant stream of information, while smart cards record trips taken, transfers, and travel patterns among transit users. Other sources of data are created by private mobility service companies operating in the public right-of-way.

Data-driven decision-making, however, has been slow to develop in transportation environments across the province. Ontario municipalities have conducted limited experiments with data-driven transportation planning over the past decade. This is partly because funding for municipalities to develop the technical means to process these data streams is not forthcoming, either at the provincial or federal level. But perhaps even more crucially, the applications for big data in transit are not yet clear to municipalities.

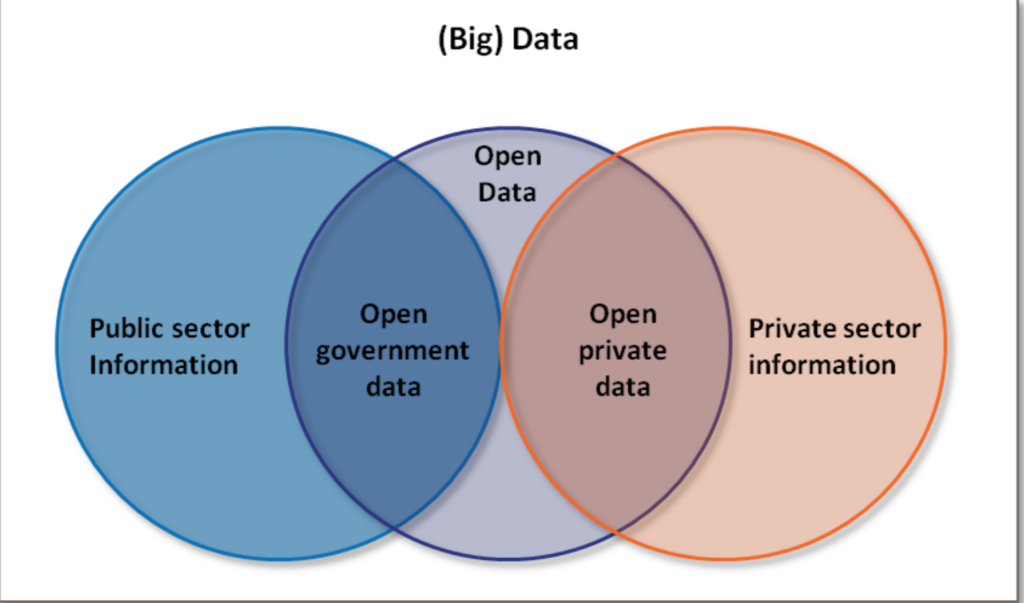

Also, new mobility providers often hesitate to share data with cities. Because private companies, from Uber to Google, control new data from moving objects (vehicles, smartphones, etc.), critics lament that cities don’t have the information they need to “ensure safety on public streets and manage and regulate transportation services to serve public goals best.”

Scholars also warn that data-driven planning technologies can further entrench inequality. This is an important threat to consider, especially because, in the absence of public capacity or strong data sharing frameworks, data-driven transportation planning would be in private companies’ hands.

There are, however, some promising developments in the province and globally. The YorkInfo Partnership brings together 9 municipalities in the York Region to develop data governance frameworks and share data, knowledge and resources to define and solve common problems. And initiatives such as the Open Transport Partnership hope to change the way big-data companies collaborate with governments by encouraging the private sector to make traffic data derived from their driver’s GPS streams open to the world under an open data license.

In the future, we should see these local-level efforts in Ontario expanded across municipalities with active support from both the provincial and federal governments.